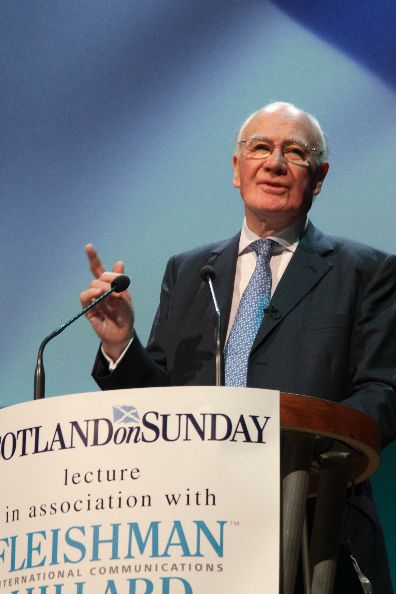

Scotland on Sunday Lecture: Holding the Government to Account, A Commentary on Chilcot

Perth Conference, Sunday 7th March 2010

Chilcot has been a long time coming. There have been other inquiries with limited remits and limited outcomes, by Lord Hutton, Lord Butler and Parliamentary Select Committees. But this is the only comprehensive investigation, with access to all the documents and all the witnesses.

It has come about because of public and Parliamentary pressure, although the government’s capitulation took most people by surprise, as did Gordon Brown’s decision to give evidence before and not after the General Election.

So unprepared was the government for its concession to an inquiry that Sir John Chilcot uniquely wrote his own terms of reference and having done so was emboldened to ignore the PM’s stipulation that proceedings should be in private. Such independence in determining the remit and that the inquiry should meet in public augurs well for the committee’s independence of mind when reaching its conclusions.

But since Gordon Brown’s appearance on Friday some of these criticisms have been renewed. The committee found it difficult to direct Mr Brown’s evidence. Of that evidence much has been written and said, not least by Nick Clegg here on Friday.

Contrary to T.S Eliot Macavity was there – but only some of the time!

Like Admiral Lord Nelson, Mr Brown saw only the signals he wanted to see. While the rest of us, including two million citizens who marched the streets in protest against military action could not help but see the storm cones over Iraq.

Mr Brown gave a confident display. But as a Scottish High Court jury will tell you, confidence and reliability in a witness are not the same thing. The Prime Minister was never really challenged, particularly on his new found justification for military action which is that an example had to be made of Saddam Hussein as a deterrent to other rogue states. It is a curious way to maintain the rule of law by flouting the authority of the United Nations and breaking the provisions of its charter which outlaw regime change.

On money for the armed forces who do you accept? Three former chiefs of the defence staff, Labour’s own defence secretary Geoff Hoon, and the senior civil servant at the time in the MOD on the one hand, or the Prime Minister on the other.

Better perhaps to ask the soldiers on the ground who had to endure soft skinned vehicles, inadequate body armour and a shortage of helicopters.

But it should be remembered that these conclusions will not simply be based on the oral evidence which has been given but upon the mass of documents, some highly classified and therefore unpublicised, to which the Committee has had access and the existence of which has been hinted at in some of the Committee’s questioning.

Most observers remain convinced of two things.

First, that the Committee would have benefited to have had among its membership a recognised international lawyer and also a former senior military commander with experience of conflict.

Advisers to the Committee there may be but these are no substitute for full membership by people with the requisite qualifications and skills.

These are not legal proceedings but they involve the giving of evidence and scrutiny by questioning. There is skill in systematic and informed questioning. By training and experience barristers – advocates in Scotland – possess this expertise. It is regrettable that no counsel was appointed to the inquiry to provide the degree of forensic scrutiny which the volume, complexity, not to say controversy of the material before the inquiry would undoubtedly justify. Had this been done then some of the early criticism of the lack of rigour in questioning might have been avoided. One critic observed that “For the most part, the Committee has been content to bowl gentle off cutters, rather than unplayable Yorkersâ€.

It is not the intention of the Chilcot Inquiry to rule on the legality of the war. This is in contrast to the recently completed Commission in Holland (which included judges) and which concluded that the Dutch decision to support the war was illegal. This decision proceeded on information provided by the United Kingdom and the USA about Iraq’s WMD programme which proved to be misleading. The distinguished UK international lawyer Philippe Sands QC who gave evidence to the Dutch inquiry described its findings of illegality as “unambiguous†and I shall return to the issue of legality later.

The Inquiry has shown up conflicts in evidence which will have to be resolved. Sir Christopher Meyer, former British Ambassador in Washington asserted that Tony Blair had “signed in blood†with George W. Bush in the spring of 2002 at the Bush family ranch to topple Saddam. This is denied by Alistair Campbell and Jonathan Powell. Clare Short contended that the Cabinet was misled over the issue of legality and that there were limited opportunities to discuss the issue. John Reid denied that this was so and said that the Cabinet had plenty of opportunity for discussion.

But much of the evidence so far has been contentious not so much in matters of fact but in interpretation. Nowhere was this more significant than in the foreword to the dossier of September 2002 and Tony Blair’s statement to the House of Commons on 24th September 2002 when he described Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction programme as “active, detailed and growing†a conclusion not justified by the evidence then available nor by subsequent investigation.

Part of this document was the so called “45 minute claim†that Saddam could launch nuclear weapons at forty five minutes notice which would threaten British forces in Cyprus. The government knew this was misinterpreted in the media and took no steps to contradict it. Added to which was of course the “dodgy dossier†of spring 2003 presented to the public with unequivocal and conspicuous authority which was later found to be based on a ten year old dissertation by a PhD student in the USA.

Sir John Scarlett head of SIS in evidence described the foreword to the September dossier as “overtly political†a euphemistic description of something, as subsequent events proved, which was a gross distortion.

Several members of the Chilcot Committee have direct experience of the proper use of intelligence. After the careful Whitehall mandarin speak of the Butler Inquiry into the use of intelligence I should be very surprised if the Committee was not more explicit in their condemnation of the misrepresentations surrounding the intelligence relating to WMD.

As the questioning of the present Prime Minister revealed on Friday the issue of equipment is firmly in the Committee’s mind. It could hardly be otherwise. The evidence given by the present Chief of the Defence Staff Sir Jock Stirrup, by General Sir Michael Walker, and by the former senior civil servant in the Ministry of Defence Sir Kevin Tebbit taken together constitutes a serious indictment of the government. Politicians all pay tribute to the armed forces when in a national emergency they risk life and limb in the national interest. But the time to pay proper tribute is when there is no emergency and the question of adequate funding for necessary equipment is under consideration. Then is the time for practical financial acknowledgement of the work of these young men and women by ensuring that they never have to make do and mend on the battle field.

Alistair Campbell in evidence and anticipation of Tony Blair’s contribution to the inquiry said “I think that Britain, far from beating ourselves up about this, should be really proud of the role that we played in changing Iraq from what it was to what it is now becomingâ€. This confident assertion ignores the costs of that change, the damage to Britain’s influence and reputation, the loss of lives and wasteful financial expenditure. But more particularly it ignores the countless numbers of Iraqi citizens who perished and the many millions whose lives have been blighted. Nor is it consistent with Jack Straw’s evidence that he deeply regrets the consequences of the military action. But it is consistent with Tony Blair’s evidence, as was no doubt intended, that the removal of Saddam Hussein was the “right thing to doâ€. The most notable feature of Mr Blair’s evidence largely went unrecognised in the indignation which so many relatives of the British soldiers who died in Iraq felt at Mr Blair’s inability to express regret for their loss. That evidence was Mr Blair’s latest justification for the military action of 2003 that action against Saddam was necessary not because of the threat he presented at the time of that action but the threat he might be presenting today. In short the action was justified in 2003 because of what might happen at some time in the future. It that was in Mr Blair’s mind in 2002 and 2003 he gave little inkling of it. If he had it would have presented even greater obstacles to legality than the course of conduct he eventually followed.

As these proceedings before the Chilcot committee have unfolded the centrality of the issue of illegality has been underscored again and again. That this is a matter of more than just lawyers was eloquently demonstrated by the spontaneous round of applause which greeted the conclusion of Miss Elizabeth Wilmshurst evidence to the inquiry – a mark of public respect for her principled resignation from the Foreign Office when it became clear that her legal advice was to be disregarded. Her evidence went right to the heart of the legal argument.

– That in her opinion military action against Iraq without specific UN authority was contrary to international law.

– That she gave this advice and it was ignored.

– That Lord Goldsmith the Attorney General was only asked for his formal legal advice after the political point of no return.

– That she counselled caution when it became clear what the consequences of military action might be.

In the essentials of that evidence she was supported by the Chief Legal Adviser to the Foreign Office who said that negative legal advice was “noted but not accepted†and that he “…considered that the use of force against Iraq in March 2003, was contrary to international law…To use force without Security Council authority would amount to the crime of aggressionâ€.

What would influence a government to reject evidence of such a nature unless there was a predetermined decision to take military action come what may. The evidence from the Foreign Office legal advisers is significant in the way its treatment illustrates the government attitude. The clear inference is that this legal advice was rejected because it did not fit with the political decisions already made.

But it is important because it was right.

Article 2 of the Charter of the United Nations forbids regime change. It is hardly surprising that it should do so because the Charter was created in the post Second World War period as a reaction against the aggression of the Axis powers. What was Nazi Germany engaged in when it invaded Poland and France but regime change? Hence a new post war political settlement to outlaw such conduct.

It is true that resolution of the Security Council may authorise the use of military force but those resolutions cannot be used to subvert the principles of the UN Charter. Nor can these resolutions authorise the use of military force unless they are written using the accepted UN language namely that “all necessary means†can be used. This is why the Security Council Resolution 1441 was defective as … authorising military action since it talked only of “serious consequencesâ€. As Robin Cook pointed out in his historic resignation speech on 17th March 2003 if Resolution 1441 provided authority for military action why was so much effort put into trying to achieve a fresh resolution. That effort was by implication an eloquent acknowledgement of the lack of authority for military action provided by 1441.

Nor do legal issues end here. It is a principle of customary international law that force may only be used as a last resort when all other political and diplomatic alternatives have been exhausted.

Albeit without the total co-operation of Iraq the UN inspectors were still able to continue their work in Iraq as the drum beat of war grew louder in Westminster and Washington. It could not be said that all diplomatic and political efforts had been exhausted so long as they were able to do so.

The absence of programmes for WMD, the purported justification for military action, was compounded by breach of the Charter of the UN, and disregard for customary international law. The illegality of the venture was manifest and manifold.

Nor are matters made any clearer by the actions of the Attorney General whose original expression of opinion reflected these principles, but whose views changed on the eve of military action in the circumstances which can only be described as controversial.

Seven years on does any of this matter? Tony Blair and George W. Bush have passed from the stage of world politics. Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice have retired from government, as has Donald Rumsfeld. President Chirac is no longer in the Elysee Palace. Why then is Chilcot important?

It is important because it illustrates the dangers of the concentration of power, the risks associated with unchallenged political dominance, the consequences of the failure of cabinet government, and the folly of the abandonment of the rule of law. If we learn nothing from Chilcot beyond these lessons it will more than have fulfilled its purpose.