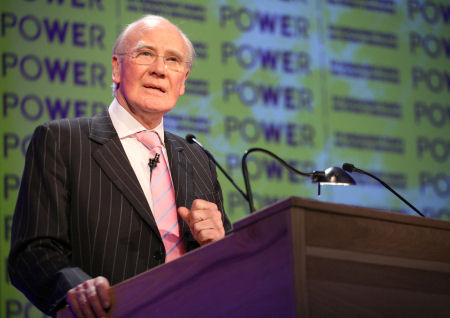

Ming Campbell addressed the Power Commission conference on May 6th, 2006 as follows:

The report of the Power Commission should worry every elected representative in Britain.

Because in their report the Commission says,

“We were struck by just how wide and deep is the contempt felt for formal politics in Britain.”

Well, that doesn’t make me feel too good, nor should it.

I can draw some small comfort from the fact that I agree with many of the sentiments and recommendations in the report.

The report describes a dysfunctional system in which disengagement has reached crisis levels.

Look at the figures:

- In recent elections, one third of the electorate do not feel represented by any of the political parties at Westminster.

- Less than one-in-five votes have had any impact on the outcome in 2001 and 2005.

- Despite a huge effort to extend postal voting, in the 2005 election, 39% of registered voters did not vote at all.

And this at a time when voter registration is at an all time low.

It is clearly a long term problem, increasingly evident since the 1960s, and one that affects not just Britain but other developed countries.

Before assuming office, the present government recognised many of the systemic failures of our democracy and committed themselves to solutions in the form of the 1997 Labour manifesto, Charter 88, and the Cook-Maclennan agreement between Labour and the Liberal Democrats on constitutional and electoral reform.

They have implemented some of what they promised – a devolved administration for Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales, and some reform of the House of Commons, under Robin Cook.

But the roadblocks to a revival of democratic participation remain – electoral reform, reform of the House of Lords and the renaissance of local government.

These tasks were urgent in 1997. Failure to accord them the appropriate urgency once more will invite a crisis in the legitimacy and credibility of our institutions themselves.

As the Power Commission makes plain, the British political system has remained more or less unchanged since the Second World War.

It is a nineteenth century system that ill serves our 21st century society.

21st century Britain is place of educated, intelligent and engaged citizens who want to know how they are governed and who want to play a part.

If we are serious about fundamental constitutional and democratic reform then we must begin with the question of empowering people as citizens, not as subjects.

As the Power Commission report makes clear, ‘the age of deference is over.’

The disengagement we have all witnessed in recent general elections and, more starkly, on Thursday, urgently calls for a new approach, a renewal of our democracy.

An underlying theme of the Power report was that people felt they were not trusted.

Not trusted to make decisions. Not trusted with the whole truth of government information. Patronised by a trivial media and treated more like consumers than citizens.

We need to trust the people of Britain more.

We need to give power back to the people.

We need to ensure that government has the support of the majority.

We need to plug the gap in accountability.

Apart from the institutions themselves, the style of governance has been distorted under New Labour.

The Power Commission calls the power grab by New Labour ‘quiet authoritarianism’, others have called it ‘creeping authoritarianism’.

But the truth is that it was almost inevitable.

Without a written constitution, the institutions and the conventions of government are open to manipulation and even to being ignored by governments with large majorities.

We live in an elective dictatorship.

Parliament has become increasingly marginalised and ignored.

Ministers and Prime Minister are immune to the House of Commons.

One hundred and forty Labour MPs are in government as Ministers or PPSs; over a third of the ruling party.

Parliament is managed and not engaged.

An electoral system which sustained a two-party dichotomy is inadequate to represent the diverse politics of the 21st century.

At the next general election, a majority in the Commons could be achieved by a party without the largest number of votes, as happened in February 1974.

Turnout, already historically low, could be even lower.

Why do we even contemplate such possibilities.

People feel powerless, they feel they have no influence over those that govern them and the decisions that affect them.

It is not only politicians who have failed but politics itself.

As the Power Report says,

“Politics has failed to bring about fundamental improvements in the lives of the disadvantaged.”

This raises the question: what is politics for?

Democracy is about giving everyone an equal say in how our collective interests are addressed and how our collective resources are spent.

Democratic power is even more unevenly distributed in the UK than income.

The recent report of the New Economics Foundation which assesses this problem in terms of an ‘Index of Democratic Power’ (IDP), concluded that less than 3% of UK voters have anything like a fair share of power.

Against this backdrop the mantra of ‘choice’ in the public services, which would treat people as consumers not citizens, appears irrelevant.

64% of voters did not want this government at all.

They did not ‘choose’ this government.

If we are serious about choice, choice must start at the ballot box.

There is a real prospect that at the next general election the abstainers will be in the majority.

The task of renewal is urgent.

The Commission’s report found that there was, “an overwhelming desire for change among the British people, but that, as yet, no clear agenda for what such a change might look like.”

It appears to me that the agenda for change is now clear, in the shape of the Commission’s recommendations.

I support them and I urge my fellow party leaders to do the same.

Let me address each of the issues identified by Power in turn.

It is comforting to hear others outside the Westminster village speaking about the need to restrain the power of the Executive.

All of the Commission’s recommendations on rebalancing power between the executive and legislative branches and between national and local government are sound.

But, in some areas the detail is thin.

The concordat is an innovative and adaptable idea to set out the competences of the different branches of government, but only as a first step to a written constitution.

Flexibility, in the hands of authoritarian governments in the future, could be readily abused.

Any constitutional settlement will require interpretation.

A job for the new Supreme Court?

Consideration of constitutional reform should include a rigorous examination of the Royal Prerogative and its unfettered use by subsequent governments.

Since before the Iraq war I have been arguing for a war powers act to require parliamentary approval for a declaration of war.

But there are other areas where the prerogative’s undemocratic reach should be curtailed: such as Treaty making.

The motion for the Second Chamber of Parliament Bill which I co-sponsored in the House of Commons is an embodiment of the reforms recommended by Power for the Lords and it is the future shape of the Lords that I would like to see.

But in the light of recent events it is impossible to consider the reform of the House of Lords independently of the issue of party finance.

The honours system and the second chamber of parliament must be disentangled.

It may well be appropriate for Honours to be in the gift of the Prime Minister subject to independent audit, but appointment to the second chamber should certainly not be.

It is perhaps worth reminding the Prime Minister that in his book ‘NEW BRITAIN – My Vision of a Young Country’, published just before his 1997 election victory, Mr Blair pledged:

“an end to hereditary peers sitting in the House of Lords as the first step to a properly directly elected second chamber, and the chance for the people to decide after the election the system by which they elect the government of the future”

It is perverse that in evidence given to the Hansard Society individual “Constituency MPs” (of all parties) are held in relatively high regard.

They are seen to be hard-working, conscientious and people of real integrity.

And yet the Commons – the collective of all those admired individuals – is seen as under the thumb of the Prime Minister or the Party Whips and incapable of its task of holding the Government to account.

The cause of this is the widespread, and accurate, perception that the institution no longer reflects the nation.

This is hardly surprising since the present government has the support of only 21.6% of those registered to vote.

An unresponsive electoral system is at the centre of this crisis of representation and the so-called ‘democratic deficit’ in Britain.

Reviving democratic participation in Britain is essential if the institutions are to maintain legitimacy, but also, if politics is to work as it should.

The argument about the Single Transferable Vote, Alternative Vote or any other voting system is not about whether it favours one party or another.

In a liberal society it can only be about how it delivers the wishes and preferences of the whole of society, particularly the disadvantaged and marginalised, into government.

Effective representation is the only way to reconnect our government with the citizens of Britain.

To improve responsiveness further and heighten accountability we need to sever other links in the political ecosystem.

And in particular, central party control over fundraising.

If parties are limited in the amount they can raise, as suggested in the Power report, they will seek to find money in other ways.

If that money is awarded through the ballot paper, then they will have to work hard for it.

This ingenious suggestion in the report, that voters indicate which party, or none, should receive a sum of money from the taxpayer when they vote, will reinvigorate local campaigning and make parties responsive to voters.

The principle that the amount should be split between local and national parties is equally neat and tailored to invigorate local democracy.

These proposals will encourage parties to break out of the current concentration on a small number of marginal seats.

My party already has well developed policy which springs from a similar diagnosis of the problems identified by the Power Commission.

And we have come to similar conclusions.

We have been at the forefront of arguing for a written constitution, for reform of the House of Lords, more powers for Select Committees and for changes to the electoral system.

But we do not rest.

Today I am announcing a new working group on citizenship and better government.

Among other things, it will be considering the proposals contained in the report.

The idea that citizens should be able to bring legislative proposals to the House of Commons is a good one and I welcome it.

Giving citizens the right to initiate hearings and public inquiries into public bodies would do much to strengthen citizens’ control over services and society as well as reducing their sense of disengagement and disenfranchisement.

The Commission found that ‘People feel disenfranchised and disenchanted because they are’.

It is not for politicians or the media to explain that feeling away, it is for us to accept the problem and look for ways of redressing the balance.

Anyone calling themselves a democrat cannot fail to seek to re-embed government in society, to refresh our systems of representation and to keep pace with the times.

If government does not represent our citizens, how can it hope to serve their needs?

I cannot stress this strongly enough.

Revitalising our democracy is not a technical discussion to be had between constitutional lawyers.

If you care about social justice, if you care about improving social mobility, tackling poverty…

…then it follows that you must care about democratic reform.

Constitutional reform is one of the hardest tasks a government can face.

It requires vision and courage to take on the vested interests within one’s own party and government.

But, as Jack Straw says in the report, ‘democracy is about giving power to those you disagree with.’

What I would like to see is not simply a process of giving power to those the government disagrees with.

But a process of giving power back to the people.

Back where it belongs.

By reasserting the sovereignty of Parliament, devolving more power to local government and enabling citizens to hold their representatives to account.

But parties should not only speak amongst and between themselves.

All of us interested in making change happen need to engage the public in the debate and spread the word.

That is why today, I am announcing an initiative to use new technology to bring these pressing political issues to a wider audience.

In the week before the three party conferences in the autumn, the Liberal Democrats will hold a virtual conference on the Power Commission proposals.

I would like to invite everyone – with any political affiliation or none – to take part in this discussion about the POWER analysis and to take advantage of the online discussion forums which we will make available through links with our party website.

We need to show the sceptics that the task is urgent.

We need to show that failure cannot be tolerated.

It is 174 years since the Great Reform Act of 1832.

The progress that has become the mark of our democratic society since that day has stalled.

It must be reinvigorated.