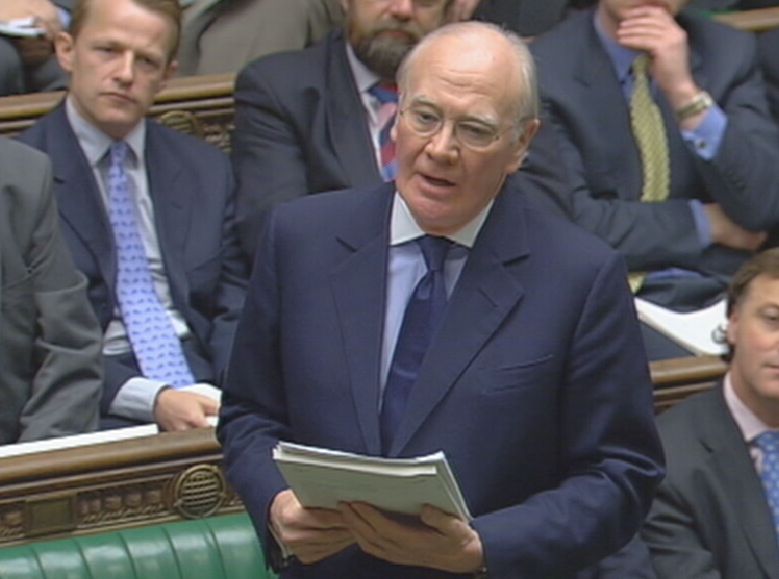

I shall vote against the Government—not because I am soft on terror or because I fail to recognise the seriousness of the threat, but because I believe that the Government’s proposals are profoundly mistaken, and that they are wrong in both principle and practice.

Much of what I might have said has already been eloquently expressed by my hon. Friend the Member for Eastleigh (Chris Huhne) and the right hon. Member for Haltemprice and Howden (David Davis). In approaching this matter, we all have a responsibility to show independent judgment, and we must exercise that judgment in striking a balance between the competing interests of security and individual freedom. If I have a criticism of the debate so far, it is that the second of these interests has formed a smaller part of our proceedings than I would have wished.

When I look across at the Labour Benches, I am reminded that for a long time Labour Members voted against the renewal of prevention of terrorism legislation so far as it applied to Northern Ireland. In 1987, after I was elected, I participated in the votes on that. In those days, Labour voted against, but then, lo, there came out of the north-east a new young shadow Home Secretary from the constituency of Sedgefield, and he persuaded his party that instead of voting against, abstention would be sufficient. My point is that Labour Members did all that through exercising their independent judgment, and we too must exercise that when the matter currently under discussion goes to the vote. My objection to the Government position has been echoed by many Members in our debate: they have simply failed to prove the case at this time for the extension of the period of detention that they seek.

I do not rely on the judgments of others. That is a kind of political card game: “You play your Lord Stevens, and I’ll play my Lord Falconer, and what did Lord Goldsmith have to say about this?â€â€”or Lord Carlile, for that matter. Such judgments may be persuasive, but they are by no means determinative of the positions we must take.

I would have had more respect for the Government if they had been willing to put their case simply, frankly and bluntly. I am not against consultation, but the scurrying around of the last few days and weeks has been demeaning to the Government, and also to Parliament. Compensation for miners is, no doubt, an extremely important issue, as is raising the economic blockade of Cuba, but what the devil have they got to do with the prevention of terrorism in the United Kingdom? Also, from where have come the allegations of Danegeld for the Democratic Unionist party? I hope that none of these stories is true; I hope that they are all the product of fevered imaginations. However, if they are part of what is necessary for the Government to have their legislation, I suspect that they are not a price worth paying.

I will vote against the Government because any time any Government seek to diminish the freedoms that are the cornerstone of our system, it is our duty collectively and individually to hold that Government to account and to subject them to the most rigorous scrutiny. That duty transcends all our other responsibilities; it is our primary duty. It is the constitutional reason why we are sent to this place, and, if I may be excused sounding somewhat flippant, I should say that it has nothing to do with the communications allowance, nothing to do with how many prepaid envelopes we use, and nothing to do with seeking to be regarded as the constituency MP of the year. Our job is to hold the Government to account and to scrutinise them as rigorously as we can. When what they are seeking to do interferes with the liberty of the citizen, that duty is even more important than it normally is.

That duty transcends the credibility, and even the survival, of the Prime Minister. This debate and the vote that we will have in due course should not be about whether he is strengthened or weakened, because the issue is whether the rights of our citizens are strengthened or weakened by what we do in this place. I shall vote against the Government, because I think that the so-called concessions are—to use less elegant language than the Joint Committee on Human Rights did—political boiler plate.

The concessions leave far too much to the discretion of the Home Secretary, they are—as the hon. and learned Member for Beaconsfield (Mr. Grieve) has pointed out in several telling interventions—complicated to the point of incomprehensibility and ambiguity, and they blur the distinction between the responsibility of Parliament and the administration of justice. If we make a judgment that it is necessary to introduce the reserve power, and if that judgment is based on the circumstances surrounding an individual case, we inevitably become engaged in the administration of justice. The inferences that may be drawn from either a willingness or an unwillingness to accept the Government’s case could be substantial in the subsequent disposal of the case against that person. I have searched my memory, and searched elsewhere, but I can think of no other instance when the House of the Commons has been called on to pass legislation based on individual circumstances after criminal proceedings have been commenced against an individual. If that is not a novel constitutional doctrine, I do not know what is.

If we want to defeat the terrorists, we have to defeat not only their wish to blow up buildings, but their wish to damage and undermine the very freedoms upon which our system is based.

The Home Secretary gave the game away earlier today when she said, “Trust me.†Of course one starts with a presumption in favour of trusting the Home Secretary, but such trust has not always been justified in every Home Secretary who has occupied that Front-Bench post since I first entered this House, and it is not likely to be justified in every future case. Parliament can exercise an informed judgment only if the information is put before it. If the information is put before Parliament in sufficient quantity, and it is of sufficient quality to enable it to exercise that judgment, that raises precisely the point that the hon. Gentleman makes: that the prejudice to the individual may be overwhelming.

Once freedoms of the kind that we are debating are removed or even diminished, they are not easily recovered. We should never imagine that what we now take for granted was handed out by benevolent monarchs or by altruistic Governments. They were won. Sometimes they had to be seized physically, and sometimes they could be seized by political or other methods. But they had to be acquired, because the natural acquisitiveness of the Executive means that it takes power to itself as often as it can. If we give the power back, how difficult will it be to restore the freedoms and the personal liberty that we regard as so important?

It is not right to legislate on the basis of what might be. It is much less right to legislate on the basis of what might be when that involves an attack on freedom and liberty. The reason why I was a little disparaging about Stevens, Falconer, Goldsmith and Carlile was that we should not be moved by the opinions of others. On an issue of this kind, we should be moved by our own judgment, and that is why I will vote against the Government.

Pingback: Top of the Blogs: The Golden Dozen #69 | Liberal Democrat Voice